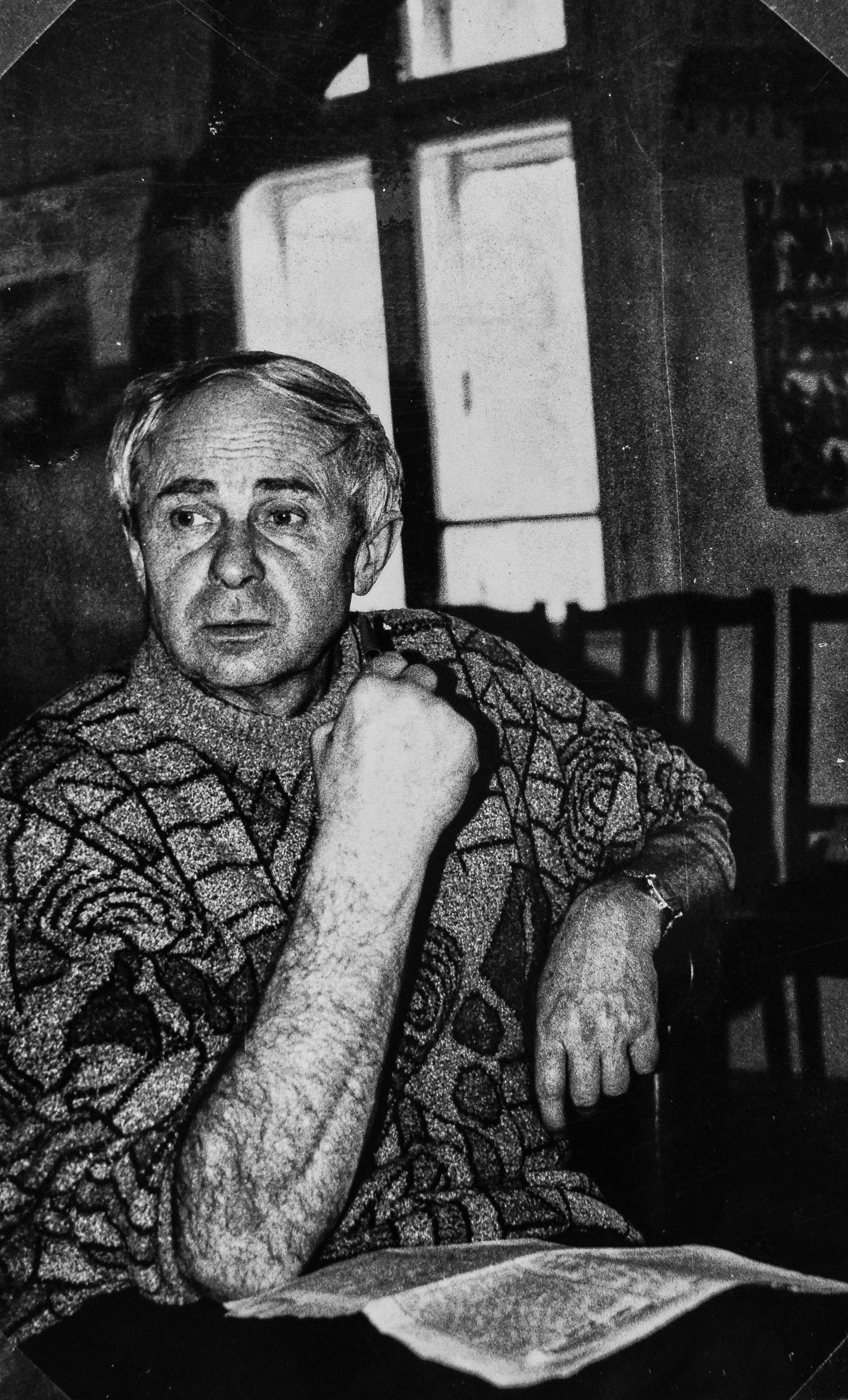

mbfitzmahan. Volodymyr Kovalchuk. Lutsk, Ukraine. 1997.

FALL 1997

A man came to the KGB office. He looked frightened. ‘My talking parrot has disappeared.’ The agent was confused. “That’s not the kind of case we handle here. Why don’t you go to the police?’ The man frowned, “I know that, but I am here to tell you officially that I disagree with the parrot.”

Viktor was a man who liked a joke. On my first day at the university, Viktor, the dean of the law school, took my hand and smiled, “I am happy you are here to help us get a new perspective. A class in comparative law is just what we need. I must warn you, though, we have no textbooks, no printer, and no computers. Sometimes we don’t even have lights,” he laughed. This time he wasn’t joking.

I came prepared to teach about American and European law, but I didn’t know anything about Ukrainian law. There was nothing written in English so I asked Viktor if he would introduce me to an attorney who could teach me a little something about Ukrainian law. “Hmmm,” he pondered. “I know! I will introduce you to Volodymyr. He’ll know what to do.”

Volodymyr Kovalchuk was neither a professor nor a lawyer. I wasn’t sure why I needed to meet him. He looked like an ordinary fellow. About 5 foot 8 with greying hair, he looked a bit like Martin Freeman in The Hobbit. He spoke English, but not fluently. How was this kind, simple man going to help me?

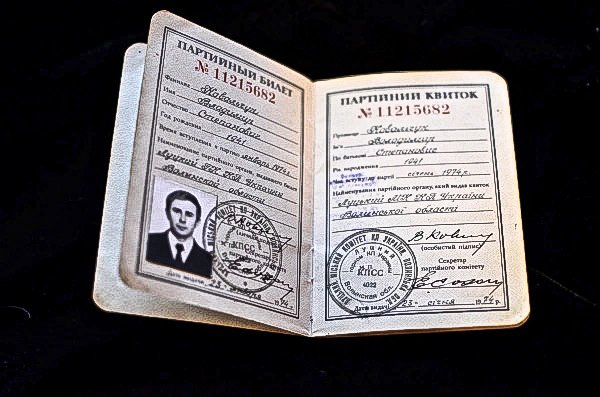

A retired communist bureaucrat, Volodymyr was a member of the Communist Party, one of a chosen few. In the late 1980s less than 4% of the Ukrainian population were members of the Party of the Soviet Union. Membership in the Party was a hard sought after honor that brought guarantees for a better job, better living quarters, and a better life.

This unassuming looking man held massive power to decide who got a passport or who did not. Many people owed Volodymyr. In Ukraine, who you knew and who owed you, were valuable commodities. A passport, a propiska, was a valuable asset when the State restricted personal movement. A passport was needed not only to travel abroad (a rare privilege), but to travel within the country – to take a trip to Kyiv, Moscow, or even to your Aunt Natasha’s in L’viv. To get a place to live, a job, or to attend a university, you needed to produce your propiska.

Volodymyr Kovalchuk‘s Communist Party Membership book.

I shook hands with Volodymr and exchanged the requisite pleasantries. Before I could explain what I needed, he looked directly in my eyes as if to weigh my commitment, “So you want to meet some attorneys. Do you also want to talk to some judges?” This would be more than I expected! Of course I did! “Do you want to know how the legal system works?” he asked. “That is precisely what I need to learn. Can you help me?” I asked. “Well, tell me. Do you want to know how the system is suppose to work, or how the system actually works?” He turned to me with that little Hobbit look, “If you want to learn how the system is suppose to work, this will take a couple of months. If you want to learn how the system really works, this could take us years.”

My modest idea to interview a handful of attorneys turned out to be a complicated, sometimes unnerving, three-year journey into the bowels of Soviet and Ukrainian jurisprudence. When I needed information, Volodymyr knew who to ask. When I needed to hear the truth, a more intricate and dangerous request, he knew how to find it.

Solely through the interview process with the help of Volodymyr, I gathered volumes of information on the new legal system of Ukraine. I ultimately compiled and analyzed the data and wrote America’s first piece of scholarship on the Ukrainian legal system, in particular its flawed court system. Columbia University published my study under the long title, “Vestiges of Soviet Control Mechanisms in the District Court of Ukraine.”

I did all my interviewing in the province of Volyn, primarily in its capital, Lutsk. Between 1997 and 2000, I met with 100 jurists and attended trials and visited jails. I did all this knowing only bits of Ukrainian and Russian.

Volodymyr taught me how to “do business” in his culture. He taught me to drink brandy in the morning with Judge Milishchuk. Vodka in the afternoon with the prison superintendent. “Chut, chut, just a little. Sto grams, 100 grams,” Volodymyr encouraged. He taught me that this was how trust and friendships were forged. “You must bring a gift, befitting the importance of the official,” Volodymyr instructed. So I took the de rigueur gift of Scotch whiskey to the judge and some cigarettes and vodka to the prison warden.

“Hide your papers,” he advised, “under the potatoes.” Volodymyr revealed the dangers to me that all Ukrainians knew. “Don’t carry around tapes of the interviews. Or your photographs. They will stop and search you.” “Who will stop me?” I asked him. “The KGB…I mean the SBU. They are the same! Absoliutno!” he warned.

Volodymyr Kovalchuk of Lutsk, Ukraine, and my friend of 20 years, died on May 1, 2017. “Volodymyr thought you were a very noble person,” my friend wrote me. “I saw him about 6 months ago. We stood outside my apartment and reminisced about those years when the Fitzmahan’s lived in our town.”

Many of my friends from Ukraine are suffering. Jobs have dried up and pensions are not sufficient to pay for retirement. Many have left and moved to other parts of Europe. Those who could not leave, stayed behind dreading a Russian invasion and feared for their survival. I will miss my friend very much. I will miss his humor, his fearlessness, and his devotion to the truth.

Since Volodymyr’s death, the Russians have invaded twice. In 2014, Putin’s troops invaded and occupied Crimea in the south as well as sent in troops to support separatists in the Donbas region in the east. This latest brutal incursion in 2022 comes as a result, in part, because the Ukrainian government has finally begun to move forward from the calamity left by the earlier Soviet/Russian occupation. Ukraine’s corrupt pro-Putin leadership was replaced in 2014 with pro-Europe leadership that made strong efforts to eliminate corruption and solidify a government committed to a liberal democracy including hopes to fix the judicial system. The latest president, Volodymr Zelensky moved to replace corrupt members of the Constitutional Court. Last year, the Prosecutor General indicted Viktor Medvedchuk for treason and attempted theft of government property in Crimea. Viktor Medvedchuk is a friend of Putin and has been identified as Putin’s choice for the next puppet leader of Ukraine.