Fifty Sounds by Polly Barton. (Note: this book will be released in the United States on August 24th.)

Fifty Sounds is written by Polly Barton, a young Japanese translator.

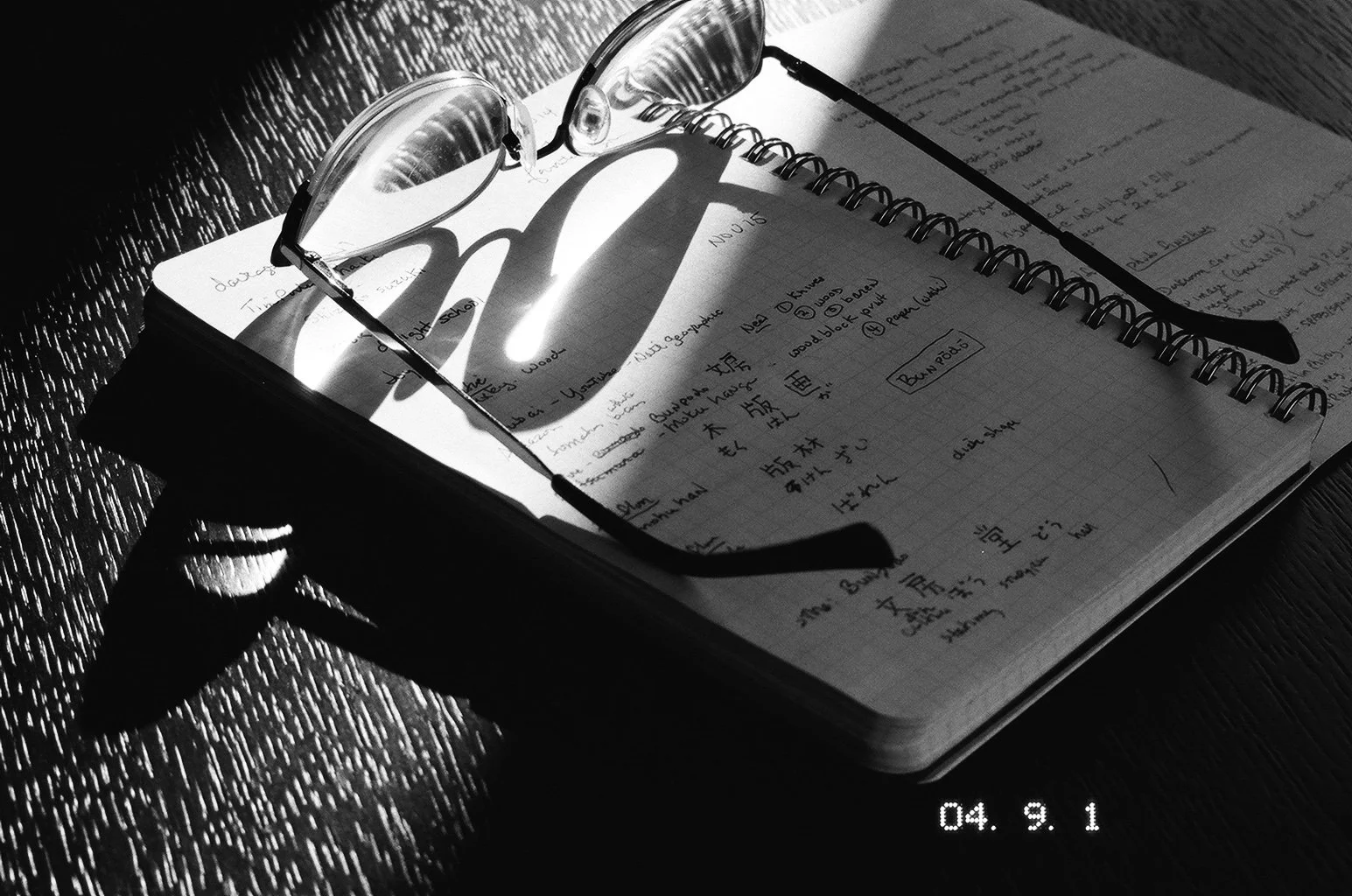

The reviews of the book warned me that this book could be mind bending. Yes, I am one of those people who reads reviews and prefaces. I also read the contents page first. And, check the Index and look at notes and often the bibliography at the end. I know, I lost you at preface. But, those who want to hold on…

“In learning a language-the experience is more akin to relearning reality and who we are in it.”

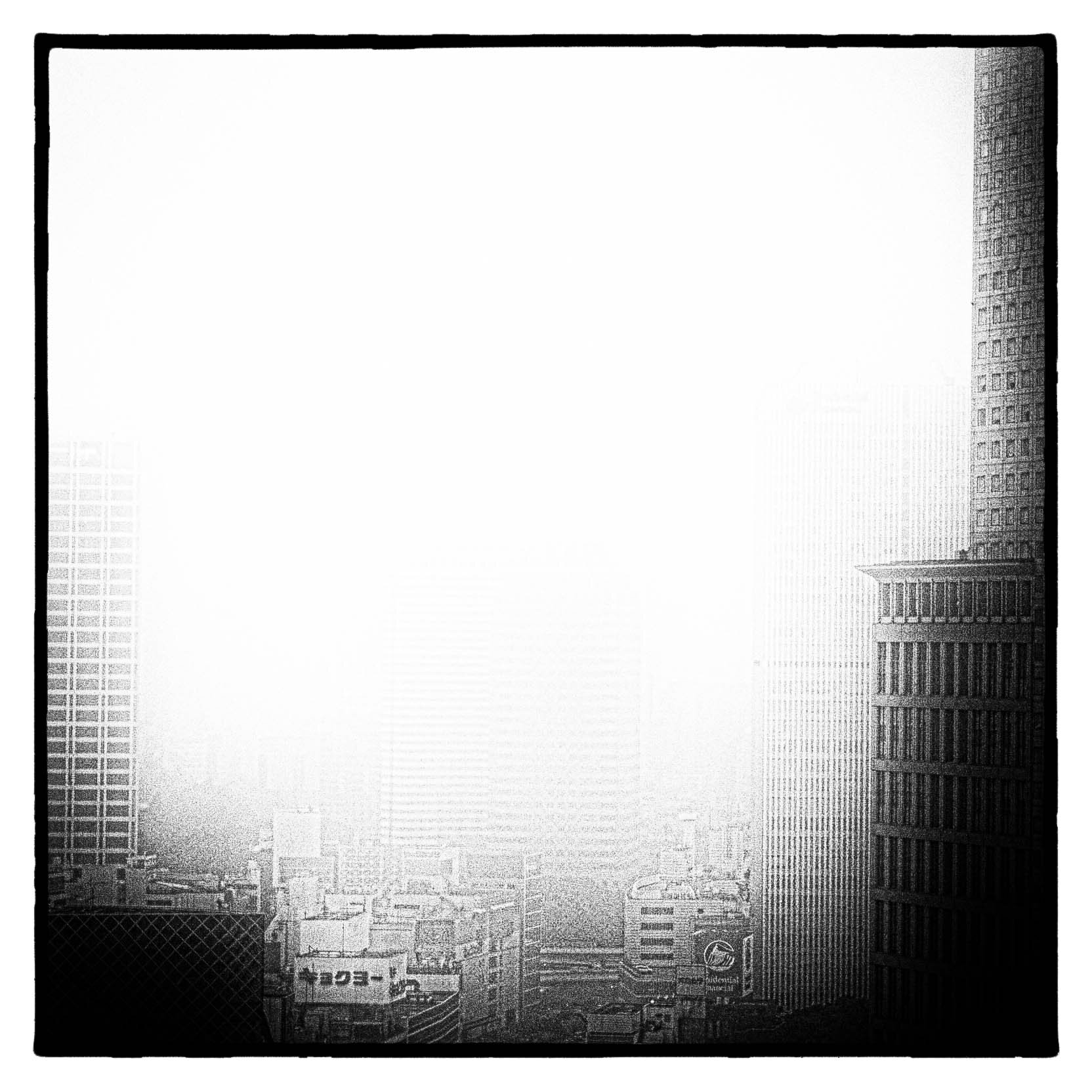

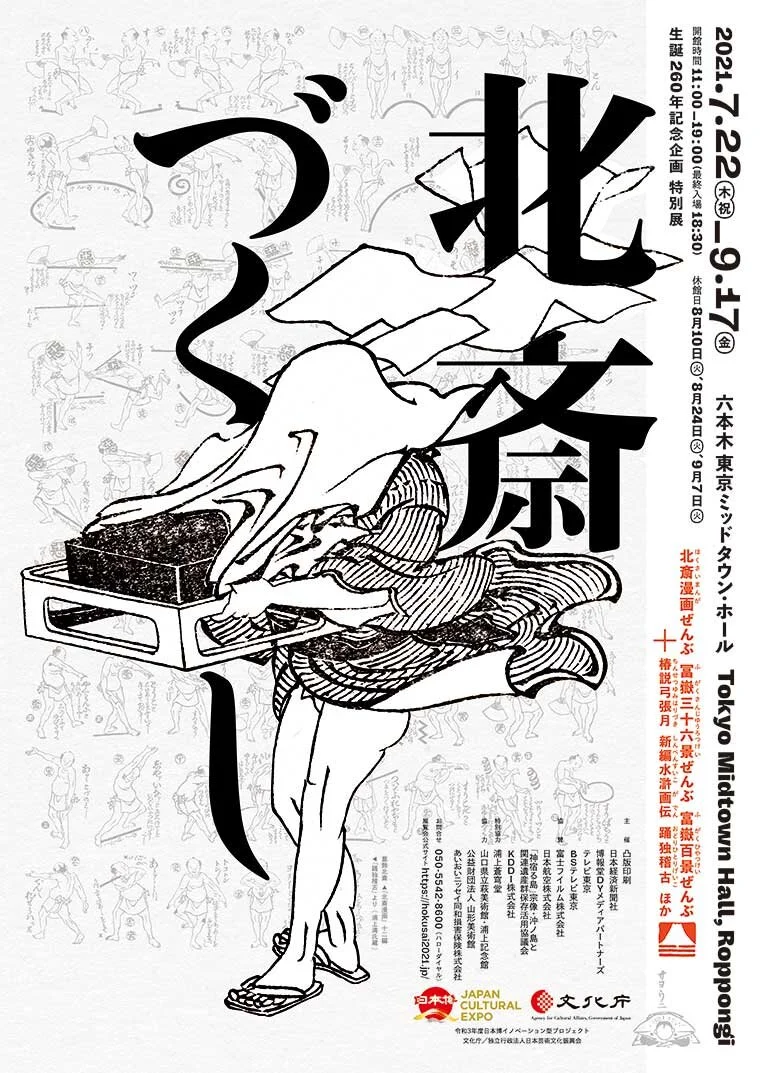

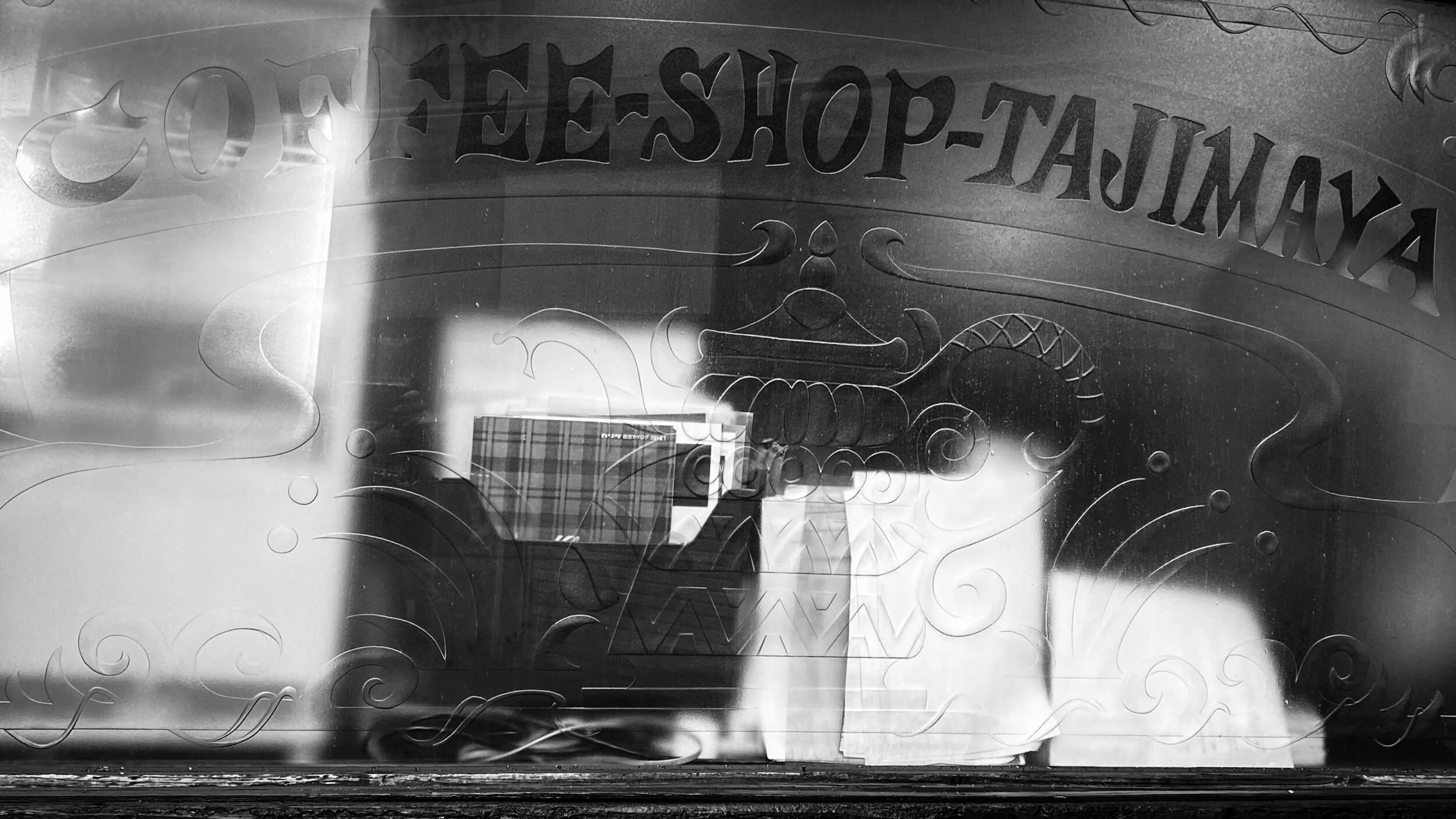

From my experience language is an insider’s code to culture. Nothing helped me understand a country as well as learning some of the language. Listen to the music that comes tumbling out of the Italian lady selling tomatoes in the market. Or the shotgun sounds emitted by the man on a telephone in Ukraine. Or cacophonous greeting of the workers in the ramen shop in Tokyo.

”Encountering and befriending a new language aren’t simply a mechanical process, but…a learning experience that is not just rationally developed, but viscerally lived.”

Have you ever felt that way about learning a language? A new language that is ‘viscerally lived.’ In your gut. In American culture and in English we speak of learning something by heart. The Japanese say in your hara. Hara translates as abdomen, one’s mind, one’s real intention, emotions. あの人は口と腹が反対です。Ano hito wa kuchi to hara ga hantai desu. This is roughly translated as, “That person is the kind of person whose mouth and stomach are opposite.”

I talked about this kind of feeling in one of my last Journal entries, Coming and Going.

I have such warm memories of Okaasan taking me to the front door and handing me my bag as I left. I’d say, “Ittemairimasu.” She would smile and say, “Itterasshai.” It was her loving way of saying, “Have a good day and discover lots, but please don’t forget to come home and see me.” Of course, every loving mother says the same to her family as they leave the house. In fact, your roommate may do the same. But, my memory is of Okaasan. Yelling out the door, itterasshai! And, no matter how late I’d return after an evening drinking and hanging out in Shinjuku, I’d hear from the back, “Tadaima!” “Welcome home, I missed you, hope you had a good day.”

The oral gymnastics of saying ittemairimasu, ‘goodbye,’ is not easy. But 50 years later, this word transports me to the little wooden house filled with tatami mats and an ofuro next to the kitchen. To the loving relationship I had with this kind woman. It isn’t the grammar or the linguistic difference of Japanese that I remember. I remember that moment.